Programming style

Before diving into the details of RAPID, it's worth discussing a few miscellaneous recommended structural and stylistic considerations that tend to result in simpler, more maintainable codebases.

Function-oriented programming¶

Function-oriented programming is simply the idea that programs should mostly be organised around functions. It's not the same thing as functional programming, in that it doesn't prescribe that functions must be pure, composable or higher-order (although all of those things might be desirable in some circumstances).

Also, in the same way that object-oriented programming doesn't preclude the use of functions, function-oriented programming doesn't preclude the use of objects. Use objects where it makes sense to do so: where a concept in the code represents an object in the real world, or where it genuinely makes sense to have both state and behaviour in the same place. Just don't use them by default for everything.

Programs that are mostly organised around functions tend to be simpler, more readable and more testable.

Python is a multi-paradigm language, supporting object-oriented, functional and imperative styles. Interestingly, these varying approaches do all tend to get used by the community, and they seem to blend together reasonably well. A quick one-off imperative script can easily be refactored to split up the code into functions, and later classes if needed.

The problem, as is often the case, is choosing which of these tools is the right one for a particular job.

Django itself is a mixed bag when it comes to picking between functional and class-oriented approaches. For example: in the database layer, tables are modelled as classes, and instances of those classes represent rows. This mostly hangs together as an abstraction1, although once you start adding bespoke behaviour things start to creak a little. We'll cover this later. Fundamentally, database models are nouns, and so the object-oriented paradigm works reasonably well.

Views, in the early days of Django, were functions. They had a simple, well-defined contract: Django passed an HttpRequest object to the view function, and the view was responsible for returning an HttpResponse. This mental model fit perfectly with the request/response design of the Web: the browser sent a request to the server, the server did some work and then returned a response to the browser. View functions transformed requests into responses.

Of course, a large part of the work of transforming a request into a response is the same across all types of request. The server needs to inspect the headers and body of the request, possibly authenticate the user using some cookie provided in the headers, check the user is authorised to do whatever it is they are trying to do, probably look up or modify some data in the database, and then render a subset of that data to HTML or JSON and return it with the correct response headers.

Django provides tools to help with each stage of this process, but assembling them all together into a view can still result in what might be called "boilerplate": the code in many views often ends up looking almost exactly the same. Maybe there's a kind of view called a "list view", which always returns a list of rows from the database. The type of object (which table is queried) might vary between views, as well as which template is rendered, and maybe how many of those items appear on each page in a paginated result set, and so on. But the fundamental flow is the same.

The first attempt at solving this "problem" was function-based generic views. Early versions of Django made extensive use of higher-order functions: functions that returned other functions. Generic views were "factories" that took some configuration parameters and returned a view function that did what you needed, without you having to fill in all that boilerplate. But, pushed to their limit, developers found that this approach often fell apart:

Quote

The problem with function-based generic views is that while they covered the simple cases well, there was no way to extend or customize them beyond some configuration options, limiting their usefulness in many real-world applications.

— Django documentation

So, Django 1.3 (released in 2011) introduced something new: class-based views (and, with them, class-based generic views).

In a way, class-based views are a bit like model classes: they subvert the usual class/instance relationship to provide a declarative API to developers. Under the hood, views are still functions, but the functions themselves are hidden from the developer. Instead, a deep inheritance hierarchy, leaning heavily on Python's support for multiple inheritance ("mixins"), are used to "wire up" the desired behaviour from a suite of smaller classes.

Reusing code via inheritance is a well-known (but fairly ubiquitous) anti-pattern. And the results in many real-world codebases are clear to see: following the flow of execution in any moderately complex view often involves jumping up and down layers between many different Python files, resulting in extreme cognitive load for developers.

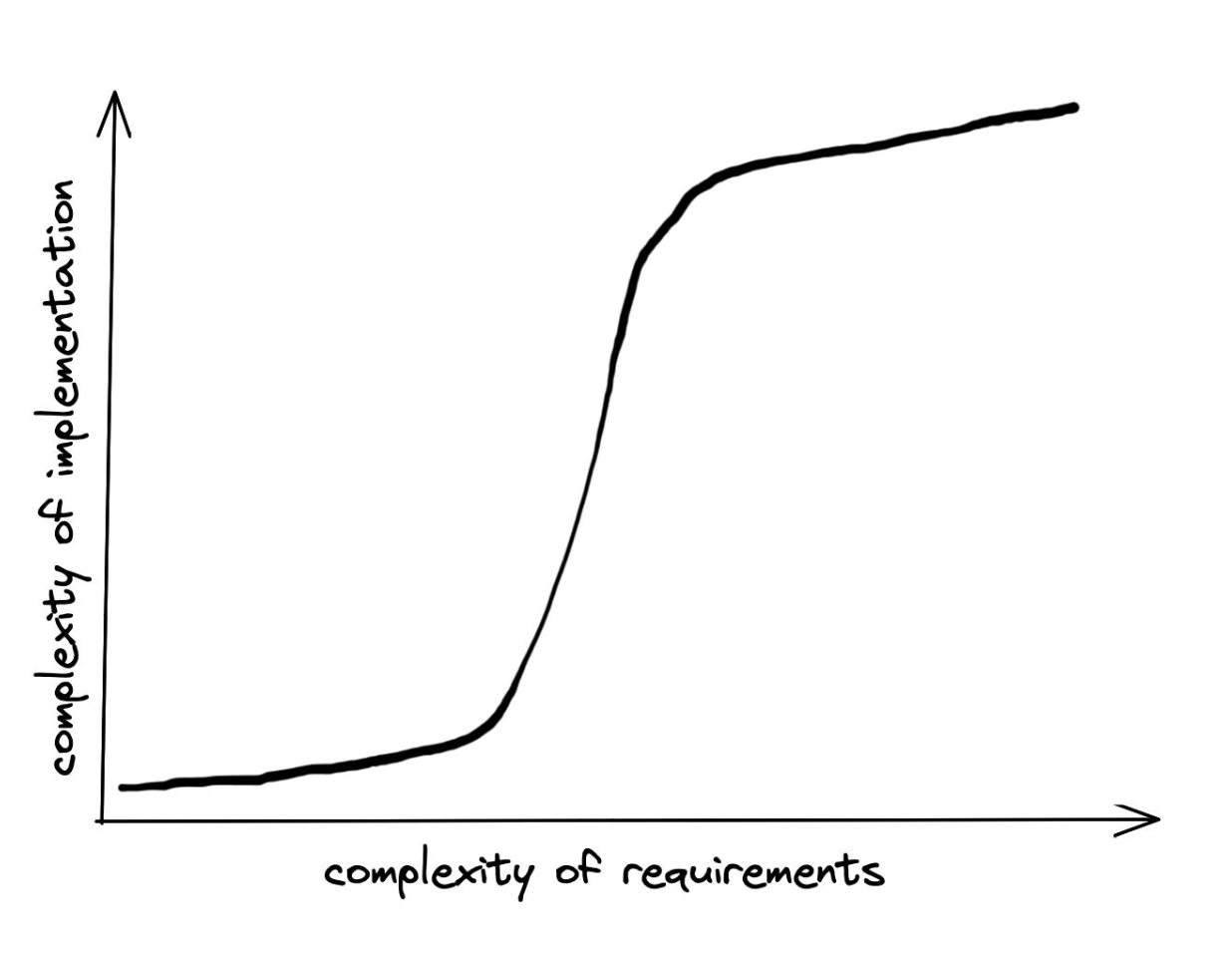

Class-based view hierarchies also tend to create complexity cliffs: discontinuities where a seemingly small behavioural change becomes disproportionately and unexpectedly difficult to make due to the architecture of the surrounding code. We'll come back to this later.

At this point I'm going to redirect the reader to another source to continue this argument: the absolutely excellent Django Views - The Right Way by Luke Plant. The arguments there are expressed far better than I could express them here.

To summarise Luke's main points:

- "Keep the view viewable" - make sure that the view function (the callable that takes an

HttpRequestand returnsHttpResponse) isn't obscured by abstraction. - Prefer function-oriented patterns (composition, higher-order functions, delegation) for HTML-on-the-server views.

- Consider class-based patterns for Django REST framework endpoints, but prefer the lower-level abstractions provided.

Views are just one example of the function-oriented pattern. My hunch is that most business logic should live in functions with clearly defined protocols. More on this later.

Abstraction and complexity cliffs¶

The topic of abstraction in software design has been discussed at length and isn't something we want to cover here in too much depth. We all know that abstraction is absolutely essential, and it's generally agreed that too much abstraction can be problematic.

To contribute sensibly to the discourse, I'd like to propose a name for a phenomenon that I see all the time in real-world codebases: the idea of a complexity cliff.

Every abstraction leaks, and when it does, you must peek "under the hood" and understand both the abstraction and the machinery it was meant to hide. A complexity cliff appears when an abstraction that has been helpful in increasing programmer velocity suddenly and unexpectedly becomes a hindrance.

We've all had the experience of building iterative features for a customer or product manager: features 1, 2 and 3 are so quick and easy to build that it almost feels like we're cheating. The library we're using gives us superpowers, we can deliver value faster than ever before.

But then feature four comes along. To a "product person", feature four doesn't feel any different to the first three. Conceptually, it's not any more complicated, it doesn't touch any more parts of the system than the last feature did. But, unbeknownst to the product person, it's against the grain of our abstraction. It doesn't fit with the mental model that we've built for the rest of the code. And so it's exponentially more complex to implement than the features that came before it. In fact, it would've been quicker overall to not use the abstraction and build everything using lower-level components. This is a complexity cliff.

There's no easy remedy to complexity cliffs, but the concept is worth keeping in mind when evaluating any new abstraction or library we add to our code. The key question is: how well exposed are the internals? Does the abstraction provide easy conceptual access to the layers between the complexity it's hiding and the interface it's presenting? Or is it a black box of incomprehensible magic?

Django itself is pretty good, in general, when it comes to risk of finding complexity cliffs. Its internals are complex, but they're largely well designed, readable, and sensibly layered. There are two exceptions that I'm very aware of: class-based generic views (discussed above), and the Django admin interface. Both of these are best avoided in projects that are likely to become large and complicated.

Type annotations¶

Static vs dynamic typing is one of those topics that tends to polarize developers, especially in Python. Some people couldn't imagine working on a large codebase without types to guide them. Others find type annotations to be syntactical line noise.

This guide doesn't have much to say on type annotations. Whether or not you use them is up to you and your team's conventions. I'll just mention one point of view that doesn't seem to be widely discussed.

When working with a framework such as Django, parts of the framework call into the code you write. For example, the framework is responsible for handling most of the work of dealing with an HTTP request, and creating higher-level representations of the request body, headers, content type etc. It then calls your code via an agreed interface or protocol: the view contract. Your code is then responsible for returning a specific object to the framework.

In both cases, technically this is a duck typed protocol: both the request and response objects just have to possess particular methods and properties for this flow to work. In practice, the protocol is quite specific about the kinds of things that are acceptable in both directions, and your code will quickly and loudly blow up at runtime if everything isn't just right.

So once a developer is familiar with these framework protocols, type annotations on those parts of the code become absolutely superfluous. Every Django developer knows that a view takes an HttpRequest and returns an HttpResponse, so annotating the view's first argument is not necessary or helpful.

The argument I'd like to make is simply: let's do more of this. The more of these "framework protocols" we can design into our code, the lower our cognitive load, because we don't even have to think about types. Rather than building abstractions with artisanal, unique, handcrafted interfaces that require type annotations to be understandable, we should aim for standard, pluggable, straightforward integration points that can be assembled like plastic bricks. A codebase designed around a small number of well-defined and straightforward protocols tends to be much easier to read and understand than even the most thoroughly type-annotated interfaces, and is also easy to learn for beginners.

Async therefore I am?¶

Python now has support for asynchronous execution, which allows I/O-bound applications to cooperatively share resources and, theoretically, handle far more concurrent connections than a program written using thread or process-based concurrency. Many newer web frameworks are built around this idea.

The problem is that, as with any technology, nothing comes for free. The benefit of increased I/O concurrency incurs a cost: significantly increased complexity, both in the execution environment and the developer's mental model of the control flow of the program.

The question for teams to answer is simply: do the benefits justify the cost? For most request/response oriented web applications, I'd argue that they don't. A synchronous programming model is so much simpler to understand and reason about that async-by-default is, usually, a horrible mistake.

Of course, if the product requires some form of live-updating with standing open connections, or is absolutely dependent on slow outgoing network requests and has very high expected traffic, then async might make sense. Django supports async views, but makes them strictly optional. Use them only when absolutely necessary.

A note on signals¶

For lack of a better place to put it, it's worth adding a small note on the topic of signals. Django's signals system is the very definition of "spooky action at a distance". Codebases that make heavy use of them tend to be almost incomprehensible: flow control is totally obscured and debugging becomes impossible. Signals should never be used to implement application-specific business logic. There are some limited situations in which they're useful for system-level configuration (see the section on models for an example), but they should be used very sparingly and with prominent health warnings.

Summary

Write code. Not too much. Mostly functions. Preferably dynamically typed. Usually synchronous.

Sources¶

- Write code. Not too much. Mostly functions. by Brandon Smith.

-

Those of us who have been using Django for years might've forgotten how deeply weird the ORM is. It's a beautiful piece of API design, but the behaviour of model classes is nothing like how objects work elsewhere in Python (or any other language, for that matter). This weirdness directly leads to other often-confusing-to-beginners concepts like managers and querysets. The fact that designing an API like this is even possible is a testament to the flexibility and dynamicity of Python, which is part of the reason for its ubiquitous success. ↩